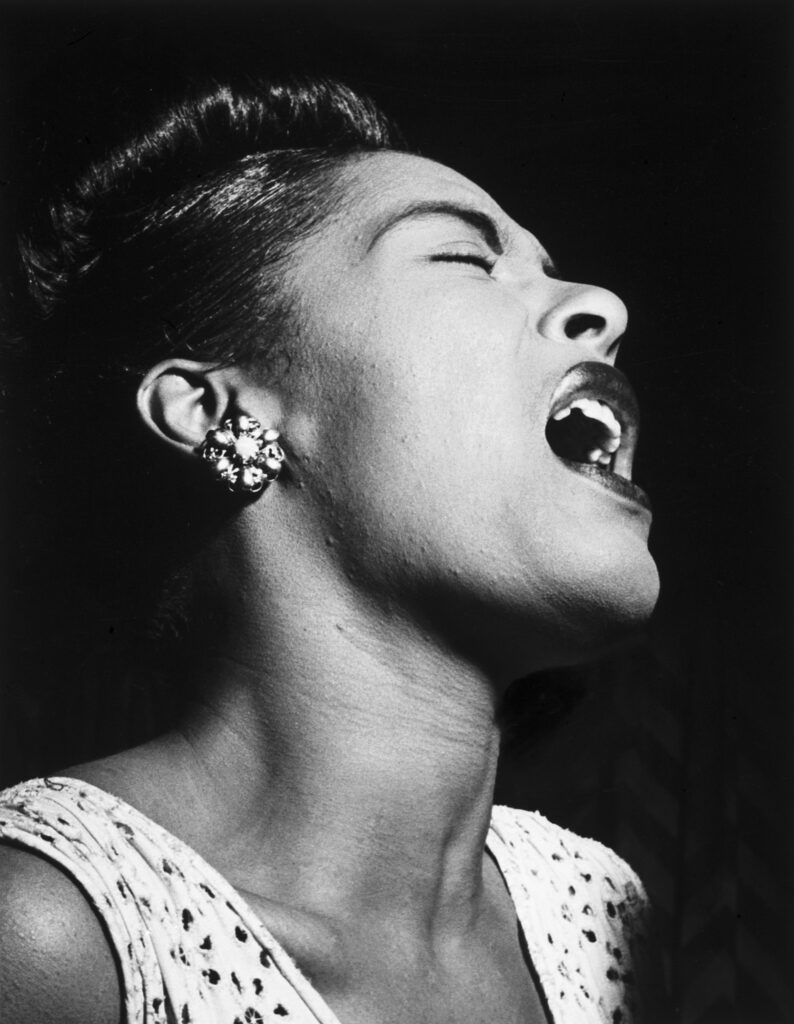

Billie’s Boy

A hidden kid gets used to seeing life from a lower point of view, and I grew up knowing people by their ankles.

I didn’t have a name; if I did, no one used it. I was just ‘Billie’s Boy’, the kid in the corner, who’d probably need picking up when the bar closed because Billie probably wouldn’t remember. This may sound like I’m complaining, and I don’t doubt it’s hard for people to understand, but being Billie’s Boy was a gift, even if she didn’t know it.

Southern trees bear a strange fruit. I was the kid no woman would admit to birthing, and no guy would own up to fathering, but times were different then. Black people were wary of white people, and I was in between the two. But Billie was Billie’s own girl, just like I was her own boy, even if she didn’t care to say so to anyone else.

You’re the sweetest thing I have ever known

and to think that you are mine alone.

My baby ears opened to her songs, every note ringing in my head clear as a Sunday bell. Hell, I knew she wasn’t singing for me, but I took the words anyway and wrapped myself up in them like a blanket, even though most days I didn’t have a bed. Unforgettable times. Those ankle bones, as black and glossy as a sherbet dipper as they walked over to me, the milky boy lying on her coat, sniffing the perfume still lingering on its collar.

When you’re growing up, you think what you see is just the way it is, for you and for everyone else in the world. The fights and the falling down dead drunk. The police calling, and Billie being away from home for weeks at a time. It was all just another part of life, like eating and sleeping. Anyway, I didn’t care because I only lived for the days when Billie sang. Maybe it seems selfish or cruel of me, but she was all I knew, her sadness dropping sweet as honey into my childish soul and making me believe nothing could be better than being Billie’s Boy. How many people can say that?

Good morning, heartache, you ole gloomy sight. Billie’s singing was more than just a pretty melody with words laced into it. Her sound was a living creature, filled to overflowing with so much pain, sorrow, joy, and love that all I could do was cry for it, those tears pouring down my coffee-coloured baby cheeks like someone had turned a tap on.

‘What you crying for Billie’s Boy?’

People started noticing me when I grew up to above their knees.

‘Hey, where the young fella come from?’

This was about the time I stopped being Billie’s Boy. Maybe it was something to do with my size seven feet and their habit of being where they shouldn’t, but I like to think it was Billie who made the change. I’d been humming one of her songs, playing the whole band with nothing more than what I had in my mouth and hands. A throat, some crooked teeth, a tongue that could spit out most any sound I wanted, and a beating drum in each finger.

Well good morning baby welcome back to town. Hear that trumpet swing. See how it lifts her and throws her high into the air with those top notes screeching like a stuck pig. The only difference is that this time it’s me who’s playing it, and Billie’s looking down at where I’m standing.

‘How’d you learn how to do that?’

‘From listenin’,’ I say, and now I’m smiling right back into her face.

‘Give the kid a trumpet,’ she says.

It’s not the first time I’ve played, but it’s the first time I been heard. So I play my heart out, and now everyone can see me, four foot high and blowing like I was ten.

‘The kid’s good.’

‘Yeh, The Kid is good.’

Over the years, I played with most of the greats. Satchmo, when he was pretty much too old to do anything else. Miles, when him calling me Kid, seemed kind of back to front, but you won’t see The Kid mentioned in any headlines because as you’ve probably gathered, I’d rather be heard than seen.

The only person I ever wanted to play for was Billie, but by the time I was ready, the drugs and booze had squeezed the life out of her. On stage, her feet were out of line, and her singing creaked like a door needing oil. Jimmy used to get mad and beat her. First Jimmy, then Joe, then Louis, the names didn’t matter anymore because it was the same old game, except that Billie didn’t want to play no more. Still, I waited, hoping that one day she’d come back, singing the blues like she used to, as rich and blood-red as the inside of an eye.

Each time I see a crowd of people

Just like a fool I stop and stare

It’s really not the proper thing to do

But maybe you’ll be there.

As a young man, you always think dying is for everyone else, but now that death has been hanging around me for a while, I suppose it’s time I gave in too. Strange how it brings you back to where you started, lying in bed and low down like a child. The nurse who looks after me is no way as beautiful as Billie, and her shoes don’t do that clickety-clackety thing the way women’s heels used to, but her ankle bones are as black and glossy as a sherbet dipper and seeing them brings back all those memories.

I’m not worrying about people grieving for me, and I’m not afraid of the moment when my eyes close for the last time, except for one thought that I can’t put to rest. The Good Lord said we can’t take our riches into heaven, which is easy said when it’s money and maybe a house, but what about the magic in my head? Who’s going to look after the songs I’ve kept alive for Billie. Billie’s gift to Billie’s boy, even if she didn’t know it.

You can help yourself, but don’t take too much

Mama may have, Papa may have

But God bless the child that’s got his own, that’s got his own. How many people can say that?