A place is a story, and stories are geography, and empathy is first of all an act of imagination, a storyteller’s art, and then a way of travelling from here to there.

Rebecca Solnit

When I think of walking, I think of the liminal space held within each stride, past, present and future suspended and then released as a flock of historical minutiae. When I prepare for a long hike, I write long lists and arrange them in order of priority from the indispensable to the inadvisable. Then I sort one from the other. When I finally lift my pack, it is considerably lighter than the first time, though now I carry a different weight. I’ve never hiked the famous Otter Trail, variously described as being harder than climbing Kilimanjaro or a walk in the park. I’ve never hiked with ten other women for five days, some of whom I’ve never met before, most of whom have known each other for years.

The Women Who Walk is a cohesive group brought together by friendship, a shared love of walking and now a single goal, to do the Otter. We’ve been training for months, some of us together, but no one thinks they’ve trained enough. I think about how I’m the oldest with the most to prove, even if only to myself.

The day comes. We’ve had the pep talk, and now we’re all standing under a wooden arch with the words Otter Trail carved into it. Photos are taken. No turning back now. I follow my co-travellers onto the trail and then slide into shadows cast by Outeniqua yellowwoods born before my grandparents. As I stroke their bark, I hope I’ll be able to recall the sensation the way I do colours.

Day one, and as to be expected, we are hesitant hikers, testing our feet and finding our places. We tread gently, soothed by the rhythmic thud of the distant ocean waves, which must be one of Earth’s oldest sounds. My anxiety, at first hot and tense, is cooled by an umbrella of green shade, but then the trail whips round to stare brazen and barefaced into the sun. Now the light dives into my pupils, arcing like dolphins. The thunder of water on rock transforms into a crescendo of applause, silver palms beating one against the other a million times in as many seconds. My heart follows. My Fitbit, my witness. I eye-trace the marked trail where it curls over, under and between boulders, daring tentative walkers like us to teeter with it. I hear my husband’s warning, be careful, but I’m long past caring and leap like a goat, not a gazelle, across the mosaic of rocks, some bigger than houses, their shades of grey lampooned by sprawling patches of ochre-shaded moss.

Then the trail mounts the last bluff and stops to stare down at the tongue of platinum blue water below.

Storms River pours the last of its past over a skyscraper-high cliff. The pool below has to be swum in, however cold. We strip, dive, scream and head for the furthest point where the water from the top meets the water at the bottom. We stand there and let the aqueous fists pummel our heads until one of us shouts, “Now!” Then we pull our costumes down and bare our breasts to the world beyond. I’ve no idea why we do it, but it makes me feel stronger.

“This is going to be good,” I message my husband later.

The walk is short from the river mouth to the Ngubu huts, where we will sleep. We unpack and find our places, then brave the cold shower that seems so much colder than the waterfall. We eat the meal that had been discussed ad nauseam for months before, though now the flavours are fresh. When I lean back to take the weight off my full stomach, a woman sitting next to me asks why I am smiling, but I can’t think of a sensible answer.

Day two. The rising sun draws scarlet curtains across an auditorium full of clouds. Nature’s celestial audience, I wonder what it will make of our show. The kitchen hut is shrouded under a cloud of aromas; coffee mingled with the sweetness of damp leaves and something else that could be visitor scat. All signs I wasn’t the only one out of bed, though, of course, the waves never sleep.

The first steep climb divides our hiker’s line, and post-breakfast banter gives way to laboured breathing, but the latticed leaves above keep us cool. In my own silent space, I wonder if the forest air should be so silent around me. Shouldn’t there be more birds? I ask later, but no one seems to know.

Then the trail summits and brings us back out into the open, where waves to our left claw the air with wet fingers. Looking down, we see how they have bored holes in the rocks. Imagine that force, I say, but no one really can.

A few metres further along the trail, I pull the Ukrainian flag out of my pack and let it fly in the wind because I want my daughter’s friends in Lviv and Kyiv to know my thoughts are with them, even though they won’t be bombed any less.

When I get up, my foot disturbs a lizard that skitters away and reminds me of the hopping hand-sized hoary toad I’d passed before but forgotten to mention until now. Pedestrians, all of us, some clumsier than others.

The summit is everything it should be, glistening, precipitous and high. We do what thousands have done before us–one group, maximum of 12 people per day since 1968, to be precise–we teeter on treacherous rocks and take hundreds of photos.

On the way down, I pass a small pile of spent gun cartridges carefully placed on a flat piece of rock, as if someone would one day come back to find them. Perhaps someone will. This is the first time I think of the Otter Trail as being one thread in a multi-coloured tapestry, but it will not be the last.

The Tsitsikamma National Park, which the Otter Trail runs through, was created according to a core mandate: the conservation of its marine and terrestrial biodiversity. And to protect the environment while encouraging nature-based tourism, the fishing and farming communities which used to live within its boundaries have been dispersed and marginalised. Where they still exist, they exist in dire poverty with no hope of relief other than the income they can earn from poaching the unsuspecting marine mollusc known as the abalone.

The demand for abalone is not local but comes from parts of Asia and, more specifically, China, where people believe the consumption of its flesh will bring good fortune and abundance, though in my view, the amounts needed to make its efficacy and longevity questionable. Over the past three decades, thousands of young men from communities along the Wild Coast have been recruited as divers and whatever other roles serve the poaching industry, which is estimated to bring in more than 3000 tonnes annually, at a value of $890 million. But the real trading hub is in Cape Town, organised by gangs whose links with the Chinese are thought to have begun with the import of methamphetamine, also known as Tik. Many of the workers are paid directly in drugs.

As I pick up a cartridge and wonder if its contents had ended up in a poacher’s body, I also remember an observation by the singer/songwriter Miho Hatori when she said, “I’m learning how to stand between two worlds: the beauty of nature and the darkness of history… sometimes the rift between them looks endless.”

The final section of our walk lifts my mood, first tracing the edge of a high cliff and then plunging into the Kleinbosh River. I’ve never really thought about why we assign genders to natural phenomena, but this stretch of water is indisputably feminine, her curves reflecting the space between a woman’s hip and waist and her lips puckering where they meet the testosterone-flooded sea. When we take off our shoes and wade through, I swear her fingers are foreplaying with my toes, or perhaps it’s just the shoals of small fish I can see.

In the morning, the trail takes us on narrow pathways that dip and crest in such quick succession our lungs and limbs can’t keep up with the changes or find time to complain. A lone gull rides the air and looks down on our clumsy progress with one glazed eye. When I slip and grab a branch, I see my father’s gnarled hand in the bark.

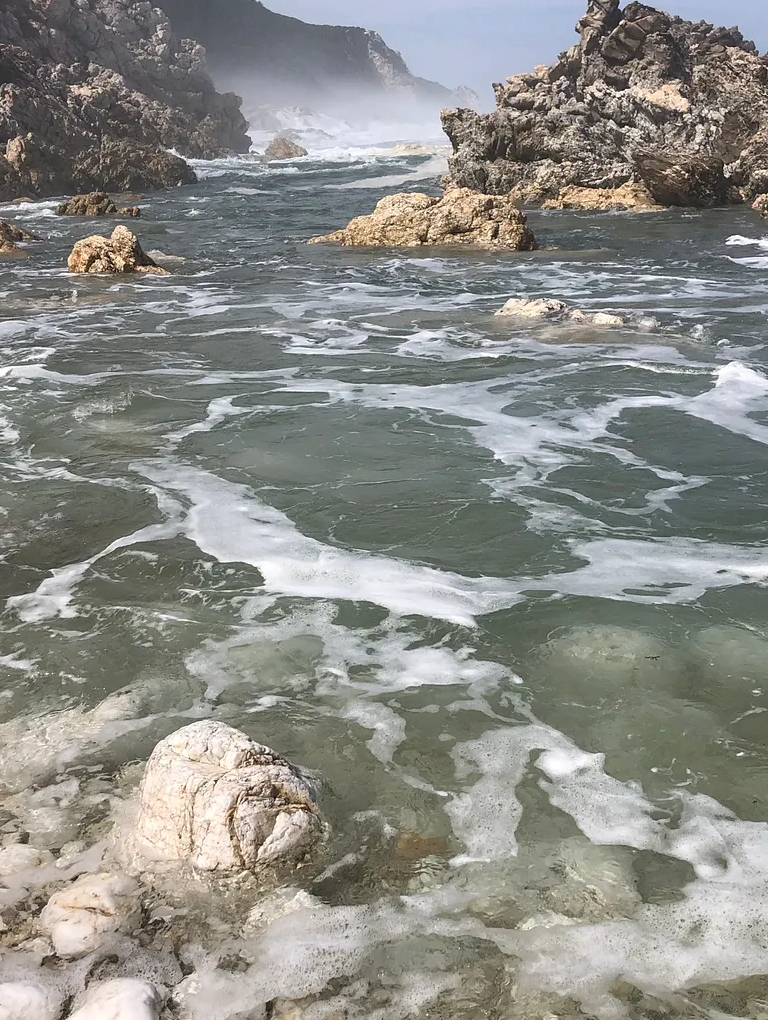

Next, we walk over, along and between the rocky spinal columns of what I imagine to be the gigantic dinosaurs who walked here before. When we rest in a small bay, waves run up the shore like crowds of children. I find it hard to believe their silky green bellies could have carved the angular shapes all around us.

Our group has become a group of inter-groups that meet and part according to the shape of the terrain. The trees are back with us, and with them, the hope to see or at least hear some of the birds we’ve been told about. The Black Oyster Catchers and Red Spurfowls were ticked off on the first day, and this morning one of us, not me, saw a Sunbird, but we’re all still waiting for the Knysna Turaco. After an hour or so of staring into the tops of trees, I look down and notice how a forest of phantasmagorical fungi is growing up from the cities of soil below. I hope Lynn, our most avid and creative photographer, won’t miss them the way I have.

We have two rivers to cross. The Elandsbos is first, and the scene is idyllic, all Lords of the Ring. For the frontrunners, the flow is reasonable. We step stone across without even removing our boots, but the tide story has already changed its plot by the time the rest of our group catches up. A chain is formed, and daypacks are passed from hand to hand and taken over the worst parts by the ones who clamber best. We should call ourselves the Women Who Work. Then we find a reasonably smooth place to rest, eat and watch the incoming current as it smashes the outgoing, like two wrestlers in a ring. I’m nervous and prefer to look down from a safe seat, but for some, the lure of blatant nature is hard to resist. A few people lower themselves to play where it’s safest. All goes well until a silver tongue of water licks them down. When they come back out, bruised, shaken but still alive, I think about how this could have been a day none of us would want to remember.

Walking again, three of our group step out and fall into what we call our flight formation, one behind the other with me at the back as the vertical stabilizer. The talk ahead is light and inclusive, but I prefer to slide inside myself — hello, it’s been too long since we had a good talk.

The Lottering River is next, and the flight formation girls move fast before its tide turns. The rest are far behind and will have to wait for the next low tide, which will be at four in the afternoon. We know they have arrived when we hear them singing on the other side of the bay.

Women Who Walk, Work and Win. We are an impressive team. Someone should have been there to film us. The tide isn’t as low as we’d hoped, but a rope and combined strength get everyone across, and everything we were most frightened of is left behind.

The Oakhurst huts are close by, and the location directly on the shore is sensational, but the showers are as cold as ever. Fires are lit for cooking and warming. We huddle, eat good food and drink our preferred alcohol. Then someone sees a dolphin, and I see a rock, which could be a seal as long as I don’t put my glasses on. The day before, Terry and Kecia had seen an otter. Later Karien spotted a bushbuck while I trod in suspiciously human-looking shit. Honestly, my mood is down because I’m missing the wildlife that should be here: genet, leopard, duiker, bushpig, badger, vervet monkey and baboon.

We leave on the fourth day, our mood sombre because we are prepared for it to be the hardest in terms of climbing and the possibly treacherous Bloukrans River crossing at the end. We have to start early and in the dark, if we are to reach the shores when the tide is out.

The first section is along a narrow path with a sheer, very long drop into the sea on one side, but we haven’t told Karien, who suffers from vertigo. Head torches on, voices low, feet placed carefully as if each step will be our last, then we pass the danger and laugh loud with relief.

The dark is thinning, more of a muslin grey than black, and from here, I prefer to turn off the torch and rely on my heightened senses of smell and hearing. We walk well; the cool air helps, and then Naomi, who is ahead, stops.

“Look!” she directs her beam down to the sandy path. “Leopard.”

I drop to my knees and hover over the indentations of a single paw print, its contours clear in the light of the still-present moon. Without Naomi’s warning, I would have walked through it. The animals are here, perhaps less than before and more in hiding, but still here.

Further along the trail, we dip down to the shoreline and find ourselves crossing a bay full of foam that covers everything like frozen waves, though, unlike bubble bath, this stuff stains our legs and boots a filthy, oily brown. I’m convinced it comes from a ship or perhaps a chemical plant further down the coast, but it’s just a freak concentration of organic matter.

As we walk out, seashells in the sand re-emerge. Lynn crouches down to take photos because some of them are so intricate and beautiful, but seeing them reminds me of how the company Shell wanted to conduct seismic surveys just a few hundred kilometres further down this same coast. In its quest for the petroleum already destroying our environment, Shell is prepared to launch blasts of sound that will impair the auditory systems of dolphins and whales who rely on their hearing to find food, communicate, and reproduce. Fortunately, Shell has been defeated by the voices of the indigenous people still living here, but I wonder what will happen if they go. The threads in this tapestry are convoluted.

From here, progress is tricky, rocks on rocks, sharp and unstable. Dassies sit up on their broad backsides in safe places to watch us stumble and slither. I used to think they were cute. I try to distract myself by resting and searching for shapes in the clouds, but when I look down at my feet, I see an eye looking up. These rocks are more than they seem.

After the rocks, the trail becomes a ladder of logs hacked into hillsides on calligraphical loops. It’s tough walking, but the vista has lifted my mood and now I feel as if I could run the whole way. Don’t stop me, don’t stop me, don’t stop me, hey, hey, hey. Don’t stop me now ’cause I’m having a good time. Of all the earworms… When I reach the bottom of the Bloukrans River valley, I strike out across the shallow water and… run.

Euphoria — a feeling or state of intense excitement and happiness. We are euphoric because the dreaded Bloukrans River is shallow, the tide is low, and all our fears about getting there too late are forgotten. We paddle and do things we probably wouldn’t do if our kids were watching, but no one cares. Then I raise the Ukrainian flag and let it fly again for our friends.

But the cliffs on the other side are less forgiving. We are confronted by a technical rock climb with just one rope hammered in to help us. We clamber up, across and back down because, by now, we are invincible. Then we walk to the Andre huts, and as we traverse the last cliffs, a crowd of cormorants straddle the skyline and open their wings to us in one perfectly synchronized movement. I think about how I could survive if life were this good all the time.

Our last day, the fifth, and the sunrise over the sea are spectacular, but why does this particular red ball in the sky seem so special? It isn’t as if I’ve never seen the show before, but I feel I’ve been reignited today. Perhaps it’s something to do with the waves throwing themselves over a colossal bank of rock in the centre of the bay without worrying about the pain or the inevitable pitching down after. Perhaps I need to be as carefree.

It’s raining, but not so heavily as to make progress uncomfortable. A flow of water on the furthest side of a small bay has started to fill, but together we find the right stones on the edge, throw them in and build the smallest of bridges. The Women Who Work.

After some beach walking, we climb into a vast area of fynbos. The name originates from an old Dutch word meaning fine bush and has since been redefined by the Afrikaaners¬ — yet another strand in South Africa’s multi-threaded tapestry. I recognize the terrain from photos and now have its sharp, herby smell stinging my nostrils. I want to stop and touch every leaf; some spiked, some rough, others like the Proteus, surprisingly fleshy. And yes, I can still remember the Outeniqua yellowwood bark on my fingers, so I’ll put these new sensations into my memory bank with it.

At the top of the cliff, we step out onto a wooden viewing platform, look across the vast ocean and then scream. I wonder how many other hikers before us have done the same.

The trail takes us a good distance along the tops of the cliffs, ensuring we will never forget our view over the Indian Ocean. Then it descends an infinite flight of wooden steps until we take the last one and plant our feet into the sand of Nature’s Valley. The euphoria is back, the rush of adrenaline that makes me want to run and run and run, but this is our last day, and there is a sadness in the feeling too. We cross the bay and turn right into the pristine indigenous forest, where I finally hear and see the elusive Knysna Turaco, not once, but four times. I can’t help thinking there is something significant in that. Our group separated into convivial twos and threes, their conversation in harmony with the forest sounds around us. I remember reading that one of the consequences of climate change is a loss of acoustic diversity, but here everyone and everything still has a voice.

The trail leads us onto a wide, wooden boardwalk that I find in some ways too comfortable, but the change leaves me free to take time and linger on elements I probably would have rushed by before: a spider’s nest shrouded in silk. A cat’s-tail-long shongololo (millipede) lounging across my path. Old Man’s beard hanging in thick laced curtains from branches festive and festooned.

As we near the end, where the last part is on a tarmac road, I walk between groups, solitary but not alone because this part of the Otter Trail tapestry is strong. As we collect our certificates, I think about the steps I have taken and which historical minutiae I should retain.

I walked with the Women Who Walk on the Otter Trail. I saw how they linked outstretched fingers across generations and cultures. Now I ask myself whose fingers I should touch and who will trust me enough to accept their grasp.

My thanks go to the WWW-ers, my signposts who walked in front, behind and alongside.

My special thanks go to Lynn Weiss, who motivated us and allowed me to share her beautiful photographs with you.